Buck’s Arguments For Slavery

The bedrock of Buck’s argument for the sinlessness of ‘slavery in the abstract’ is that ‘God approves of that system of things which, under the circumstances, is best calculated to promote the holiness and happiness of men’ (Buck, 5). He provides various proofs to show that, in its ideal state, slavery was designed to promote the holiness and happiness of the slaves. He argues that slavery was introduced to Abraham as a system to protect ‘the helpless and oppressed’ (Buck, 6). This system was designed by God to ‘benefit the slaves and not Abraham’ (Buck, 10). Likewise, Buck argues that American ‘slavery has been less beneficial to the whites than the blacks’ (Buck, 27). This balance of benefit is accomplished because slavery incentivizes masters to care for the disenfranchised instead of dismissing them as someone else’s problem and leaving them to starve. By Buck’s assessment, nations and states with slavery have less ‘destitution and suffering’ than those without slavery (Buck, 13).

Buck also argues that the Bible sanctions slavery. He draws this conclusion from biblical accounts indicating that Abraham owned slaves and God’s command to Hagar to return to her mistress (Buck, 9). Since Abraham is held up as an example of moral purity, his status as a slaveholder acts as a divine blessing on the institution. Buck draws a similar lesson from the story of the Gibeonites who were made slaves in Israel instead of being destroyed (Buck, 11). These references are not simply hired servants since hired servants are often distinguished in the text from purchased slaves. Buck argues that it is morally acceptable to own other humans because man-servants and maid-servants are not distinguished in the Decalogue from other ‘articles of property’ (Buck, 10). Since ‘slavery was sanctioned by the law Moses’ then the abstract act of either buying or holding a slave cannot be sin’ (Buck, 21).

Buck admits that slavery ‘has been awfully perverted and abused’ but does not think that the abuses and perversions of slavery reflect the morality of the institution itself (Buck, 12). He argues that condemning slavery for its abuses means we must also condemn marriage because wicked men have perverted it (Buck, 22). Rather, Buck asserts that God is working through the evil intentions of men and turning them for good, just he did when he led Joseph into slavery in Egypt (Buck, 24). Buck sees the ultimate goal of slavery as the improvement of the slaves in preparation for the government-funded liberation and resettlement of qualified slaves in Liberia (Buck, 26). He believes that African slaves are quickly improving and will soon be ready for ‘self-government and national independence’ (Buck, 22). Buck also challenges the idea that all slave traders and slave owners work from sinful motives. Slave trading does not qualify as man-stealing because Africans are first enslaved by their own people through consensual wars of conquest before being brought across the Atlantic (Buck, 16). He also condemns those who purchase slaves for the sole purpose of ‘enriching themselves’ while proposing two other classes of slave traders and owners who work from commendable motives. One class acquires slaves out of a ‘desire to promote their social and moral improvement’ while the other is motivated to ‘instruct them into the knowledge of salvation by Christ Jesus’ (Buck, 17-18). Buck believes that these slave owners will gladly surrender their slaves once they have been ‘sufficiently enlightened to return to Africa and govern themselves’ (Buck, 18).

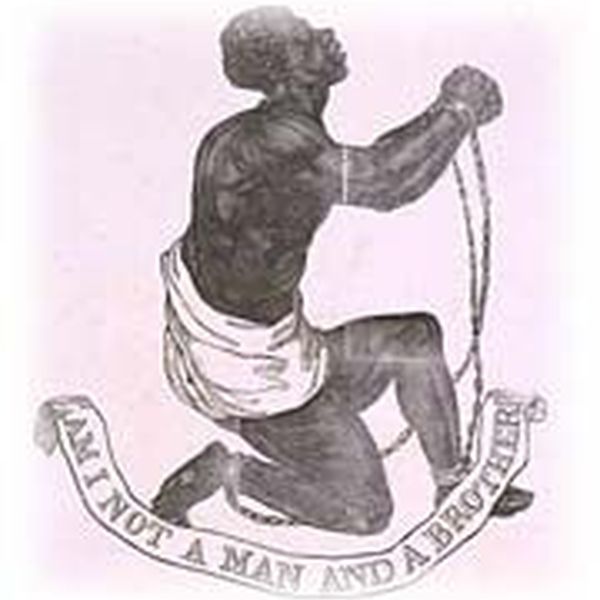

Pendleton’s Arguments Against Slavery

Pendleton agrees with Buck’s premise that ‘God approves of that system of things which, under the circumstances, is best calculated to promote the holiness and happiness of men’ but argues that slavery ‘does not promote the holiness and happiness’ of either race (Pendleton, 2). This is supported by Buck’s own assessment of the ‘pernicious influence’ slavery has over the ‘moral interests’ of white people and fact that slavery promotes the ignorance of the slaves (Pendleton, 2-3). Attacks on the ‘holiness and happiness of men’ are seen in the fact that state law allows slaveholders to ‘sever the marriage tie’ between slaves, separate slave parents and children, and ‘prevent their slaves from ever learning to read the Bible, or from hearing the Gospel preached’ (Pendleton, 1-2). The American system ‘depends on the ignorance of the enslaved’ which does injury to ‘the immortal mind’ of human being and points to the fact that there is ‘some antagonism between the Bible and slavery’ (Pendleton 8-9).

Pendleton also argues that the Bible does not condone slavery, especially the form of slavery found in the American context. After showing that the word ‘slave’ is never directly used in the Bible, Pendleton enumerate ‘points of material dissimilarity between that system and our system of slavery’ (Pendleton 3). One dissimilarity is Abraham’s willingness to arm his slaves in Genesis 14; something that would never happen in the American context. It is also difficult to reconcile American slavery with Abrahams expectation that a slave would be his heir if he was to die childless (Pendleton 4).

Pendleton also points to the stipulations in the Mosaic law that set Israelite slavery apart from the American context. These stipulations include the penalty of death for anyone guilt of man-stealing, which is how Africans were ‘first introduced into this country,’ and the guarantee of freedom for any servant who suffers serious bodily injury ‘inflicted on him by his master’ (Pendleton 5). The law also forbids ‘the delivery of a runaway servant to his master’ and makes provision for regular worship, rest, and emancipation for slaves (Pendleton, 5). Nevertheless, Pendleton argues that, even if American slavery was similar to Abrahamic slavery, it would still not be morally acceptable. Abraham committed many condemnable acts, including deception and sexual impropriety, which keep him from being used as an absolute moral example (Pendleton 4). The presence of slavery in the Mosaic law is unique to the Jewish context and was to ‘keep the Jews a distinct people’ (Pendleton, 5). The permission to hold slaves is nowhere extended in Scripture to the ‘Gentile nations’ (Pendleton, 5).

Pendleton also points to the abuses found in slavery and its negative effect on all involved as a reason to end it. He asserts that slavery’s ‘perversion is extensive’ in both state laws and the practice American slaveholders (Pendleton, 11). Nearly all slaveholders are seeking their own ‘pecuniary interest, and not the good of the slaves’ to the extent that slavery could not continue without the abuses that are condoned by the law (Pendleton, 8). This point is illustrated by the fact that pro-slavery advocates acknowledge the evils and abuses of slavery but do not want the laws to change to correct them (Pendleton, 11). By trying to justify slavery ‘in the abstract’ without addressing ‘slavery in the concrete’ slavery advocates work to entrench the very the abuses and perversions they decry as evil (Pendleton, 9).

Response to the Slavery Debate

Buck and Pendleton hold conflicting presuppositions about the nature of the slavery debate. Buck believes that the debate must be centered around the morality of slavery ‘in the abstract.’ This allows Buck to acknowledge abuse and systemic perversion in the American system of slavery but treat those issues as separate and unrelated to the core debate. Pendleton insists that slavery ‘in the concrete’ is what must be evaluated. He deals directly with the realities of slavery, showing that the system itself is corrupt and evil. Both men agree that slavery must ‘promote the holiness and happiness of men’ to be considered ‘morally right’ but Buck’s arguments focus on the morality of a hypothetical ideal while Pendleton dissects the system as it stands. Buck’s focus on an abstraction of slavery, however, is not absolute. He makes several attempts to justify the current practice of slavery, appealing to exaggerated claims about generosity and goodwill of slaveholders. Instead of supporting his theses, the need to make these claims actually undercuts his premise and exposes the disconnect between the morality of slavery in the abstract and morality of the system that actually exists.

Buck and Pendleton also take different approaches to interpret and understand the patriarchs and the applicability of the social and civil laws of Israel. Buck invokes the Mosaic law to justify his position on slavery, but Pendleton effectively shows the weakness of his approach. Buck’s approach to interpreting the Old Testament takes passages out of context and applies them in favor of this position. When citing the Mosaic law, he appropriates the sections that allow slavery but does not advocate conforming state law to reflect the actual Mosaic system, which contains safeguards that promote the well-being of slaves. Pendleton’s approach to the Old Testament law does not try to appropriate it directly but takes into account the law’s unique role in the life of Israel, setting it apart from the surrounding nations as a covenant community. A similar pattern is seen in Buck’s interpretation of the story of the Gibeonites. He interprets their enslavement as a gracious act approved by God but ignores the context of the story, which shows that the actions were actually an ‘ignorant violation of the positive command of God’ (Pendleton 4).

Conclusion: Biblical Arguments on Slavery

This paper showed that Buck and Pendleton reached different conclusions about the morality of slavery because they began with conflicting presuppositions about the nature of the debate and handled the context of Scripture differently. This was accomplished by looking at each man’s arguments about the effect of slavery on the holiness and happiness of men, it’s treatment in the Bible, and the significance of abuse in the American system and concluded by comparing Buck and Pendleton’s presuppositions and their handling of biblical context. Understanding the nature of this debate is important as we seek to interpret and apply Scripture to modern issues and debates.